The Unreal Writer

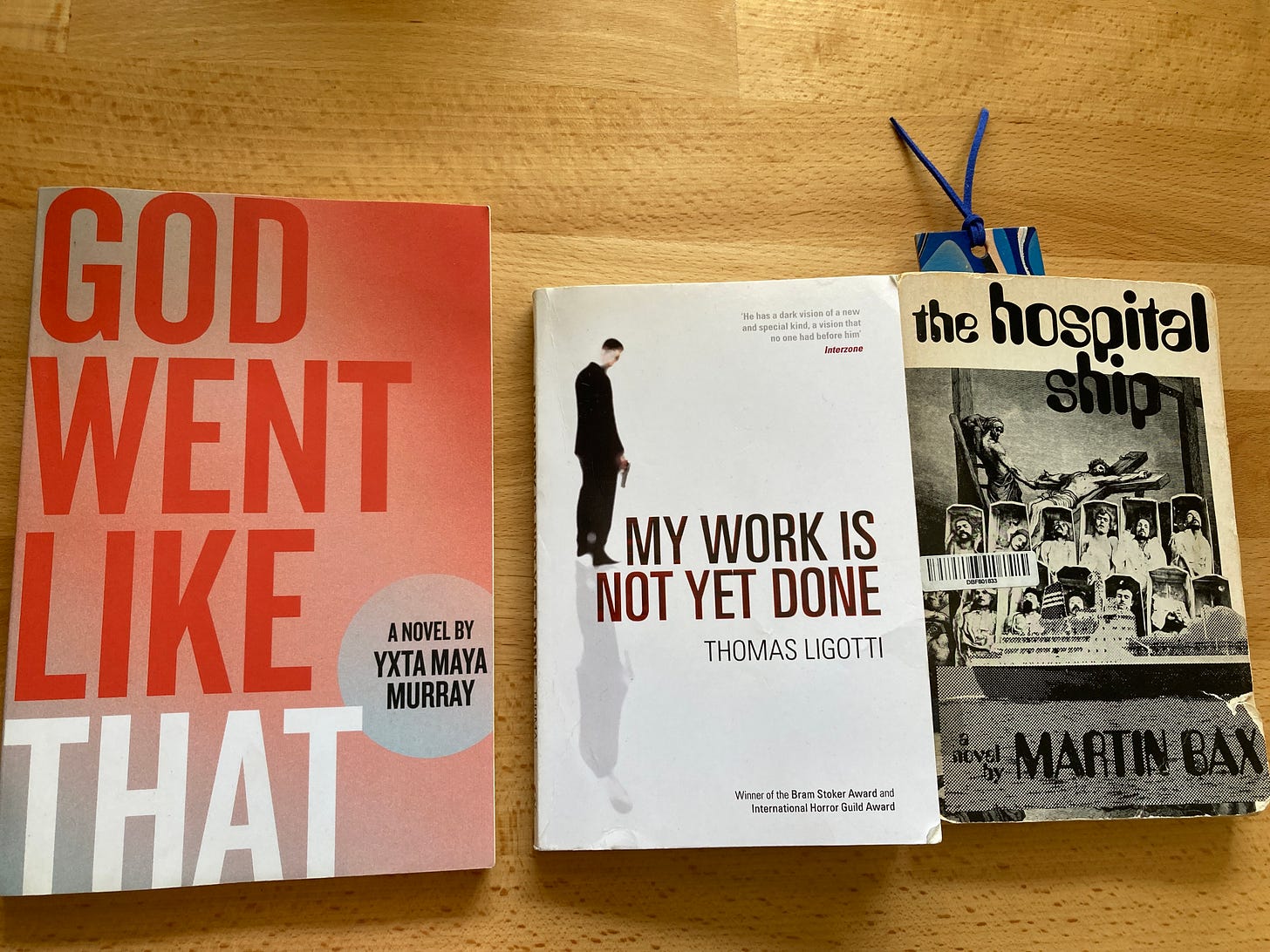

Excited to dig into this, my most recent 3am Alibris order:

Somewhere recently, I read an interview with an interior designer who said something like, “if you really love a piece of furniture, the style will always work in your home.” The notion being that your are your own through-line, you are the current: your taste and judgement is how everything in a room—your room—hangs together. Wish I could find it now (or maybe it’s common wisdom in design?) At any rate, I keep thinking about it as this advice might just as well apply to writing a book.

God Went Like That by Yxta Maya Murray might be my favorite novel this year. It’s structured as collected testimonies from people impacted by the Santa Susana Field Laboratory including the nuclear reactor meltdown. I’m ordinarily weary of novels with alternating narration but Murray builds on the story with each chapter. The writing is stunning and she reveals something of the characters in five to ten pages that other writers might need an entire novel to feel earned. Claws deep at the blinked pursuit of scientific knowledge and its human costs.

My Work is Not Yet Done is the first thing by Thomas Ligotti that I’ve read. I suspect this isn’t the best place to start with him, but it’s good enough for me. I watched Beau is Afraid the other week, and everything else on my bookshelf felt incredibly conventional in comparison. Not quite to my tastes, but intrigued by it.

And I’d been meaning to read Martin Bax’s The Hospital Ship for, well, the past twenty years because JG Ballard recommended it (and Bax founded Ambit), but in this instance the past six months. I’d pick it up and marvel at the cover and admire the first several pages, and then, I'd just bounce off it. Something about Bax's style struck me as too lush and my mind would begin to wander before I made it to the next chapter. That was even before the fake medical reports and other dry found texts that chop up the narrative. Well, I stuck with it this time and I’m glad I did because it's one of the most charmingly and ambitiously stupid and incomprehensible novels I've ever read. It’s about the world and humanity but really it’s about the pleasures of of “big” and “chunky” blonde nurses. And it’s written in a swirly style with hesitant interiority that leaks out between the info-dumps. The back and forth from technical writing to stream of consciousness annoyed me until I realized the dry parts probably worked as intellectual scaffolding that freed the author to write all the wild stuff about the nurses. Anyway, it’s always great to be reminded that once there was a science fiction literature that wasn’t driven by saves-the-cat formulas, “inciting incidents” and rising-action-climax-falling-action story mechanics

#

Something I don’t necessarily believe but I think I could argue convincingly is that if you are really looking for the Octavia Butlers or the JG Ballards of today, the only place you’ll find them is romance genre.

It is the one genre left that has evaded mainstream acceptance. It’s a genre that authors of “literary” work never dabble with—well, never confess to, as a foot in that world would besmirch their reputations. Romance writers work outside traditional measures of literary prestige. Their books might be reviewed in the New York Times but only in a quarantined box alerting readers in advance like a content warning. To be clear: the reason I can’t and won’t make this case is I don’t know anything about romance writing other than its lack of respect commands a great deal of respect from me. Which is to say, I’m myself too much of a snob to know what a romance lit avant-guard would look like or if it’s happening.

Science fiction had always appealed to me as the genre of losers. The white maleness of it all was something I struggled with, but almost as much, I struggle now with the style of, you know…those books that are like, “five diverse young women have just graduated from the galaxy’s most technically rigorous astronaut training program. Can these ultra-elite feminist techno-astronauts save humanity from environmental collapse with their brilliance and extraordinary gifts?”

I suspect those authors are drawn to the genre for the thing that increasingly frustrates me about it: the way science fiction is mined for road maps and potential solutions in real situations of uncertainty and disaster. The way it’s “smart person” literature about systems with hyper-competent protagonists. I’m here for the losers. The losers are my people.

In quite a few interviews and essays by Ursula Le Guin, you can see how slighted she felt through much of her career, that literary establishment refused to take science fiction writing seriously or read it on its merits and intentions. Obviously the prestige and mainstream acceptance arrived over the course of the past two decades—especially for Le Guin—but at a cost, these new readers tend to straightjacket what’s interesting about the genre.

I’m regularly baffled by writing about Philip K Dick, especially, by mainstream literary critics. The man was a serious weirdo and very frequently hilarious (and, yes, problematic). He was always writing from another planet. But to be legible to scholars and critics, they construct a character out of his legacy: a serious man, who was part of counterculture, with a clear-eyed prophetic and ultimately useful view to the future. In their mind, he was the sort of person who could show up on NPR and tell us exactly what the world is like and where it’s going in super clean—not at all rambling or paranoid—tape. (Although, “not a great prose stylist” these types love to say—wrong on that too, on a line level A Scanner Darkly is fucking electric). This is happening with Octavia Butler in real time. Her daring and the moral complexity of her characters is swept away in recent assessments to create a coherent legacy—that of an earth mother tote bag caricature-icon. This is reading authors as flap copy, accessing the top layer of the writing, and refusing to convene with the messy human elements in the work. What are their books—any books—even for, other than for us to approach as humans, wandering around with their words and experience the extraordinary workings of another human’s mind?

The snobbery against science fiction in the past and today’s cartoon icons of some of its weirdest authors comes from the same root: an establishment that doesn’t know how to read or appreciate it. The establishment needs the work digestible as buzzy fragments. The feral elements in what are now science fiction classics—the originality and experimentation—isn’t legible to them; which means even the most famous authors, when you encounter the work on your own, are likely to surprise you. Their mysteries as authors remain mysteries and to a more generous reader—that mystery is exactly what hooks you.

Literary fiction, meanwhile, has entrenched dependence on shorthands to determine the merit of a work before it’s even read. I’d never in my life heard the word “pedigree” used in any conversation that wasn’t about dogs until I met people in publishing. There are frightening rituals of pre-screening, pre-reading of an authors—especially women authors. Where you went to school, who your parents are—all of this is irrelevant to the integrity of the work, but it is in the service of the creation of the mystique of a writer, the mystique of a “Real Writer.” There are specific magazines that a Real Writer writes for, friends and alliances they make, parties they attend (the right parties). It’s ultra-specific and not worth naming what are considered “real” institutions and cohorts. The flip-side of Real Writer reputation building and myth-creation is what we could call the Unreal Writer, who is anything but these things. And that’s most of us—especially the most of us who do not come from money.

What’s on offer in a book is only ever the book rather than a sillage of importance that blows from the author to the reader. But what a book is for a Real Writer is a mechanism to succeed, a means to satisfy an ambition that’s entwined with a need for external validation. If you enter through the “Real Writer” gates producing work that is “real,” there is only so much you can do from there. By narrowing the field—to the terms of what’s real writing or not real—they are stuck in their own crumbling castles. It’s only those working outside these castles who can subvert them, out run them.

I think about this a lot because I can only ever be an Unreal Writer. I’m unreal as a writer of fiction because I published a work of nonfiction before it. Before that book, I was unreal as a nonfiction writer because I had a blog and I wrote on the internet (this is not how it’s done, it’s utterly unreal of me). The sheltered voice of Real Writers of literary fiction is something I do not like nor aspire to mimic. That too makes me unreal: I’m working class and a leftist and someone who has no respect for—let alone engagement with—elite education in the United States. And always when I think about it, I come back to the belief that to be a Real Writer is a creative dead end.

Anyway, maybe I’m rambling here and revealing too much of my own writerly insecurities. I feel some temptation to press delete but fuck it, I’m about to smash that send button.

#

On that note: I’d love it if you’d please pre-order my extremely unreal novel, WRONG WAY (or request a copy from your local library).

Thanks for reading.